Eleanor Roosevelt and U.S. Secretary Of State Dean Acheson at the United Nations General Assembly in Paris, Nov. 9, 1951.

Whatever we think of the United Nations, its establishment in 1945 remains a turning point in the history of contemporary international relations. Of all the volumes written that recount this story, one of the classics remains Dean Acheson’s memoirs, Present at the Creation: My Years in the State Department (winner of the 1970 History Pulitzer prize).

Despite the mind-numbingly boring and actually confusing title (Acheson is referring not to the creation of the U.S. Department of State—that was in 1789—but to the creation of the post-war American-led international order), the book is a revealing account by one of the most influential diplomats of his age. Secretary of State under President Truman from 1949 to 1953, and an active advisor to many occupants of the White House afterwards, Acheson was directly involved in the forging of a new post-war world in which the United States was the new dominant power, and intent on taking the stewardship of the international system.

I was drawn to retrieving this yellowing memoir from my library (currently a pile of perilously stacked up cardboard boxes in my future home), as a look back at the year 2023 led me to the sad thought that, if I were to write my own memoirs as a human rights professional, the title could be: Present at the Destruction: My Years in International Human Rights.

For 2023, and, for that matter, the last few years have not been kind to the lofty goals that presided over the creation of the post-war international system, which were, in the words of the Preamble of the UN Charter:

“[T]o save succeeding generations from the scourge of war (…) and to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small, and to establish conditions under which justice and respect for the obligations arising from treaties and other sources of international law can be maintained”.

From the human and physical devastation of Gaza to the burned down villages of Darfur, from the razed-down cities of Yemen to the overflowing prisons of Egypt, from the trenches of the Ukraine war to the mass internment camps of Xinjiang, from ever-increasing millions fleeing conflict, violence and poverty to the West’s failure to agree to pay reparations for the impact of climate change for vulnerable countries, there is hardly any crisis that doesn’t point at the crumbling of the better ambitions of the postwar international order.

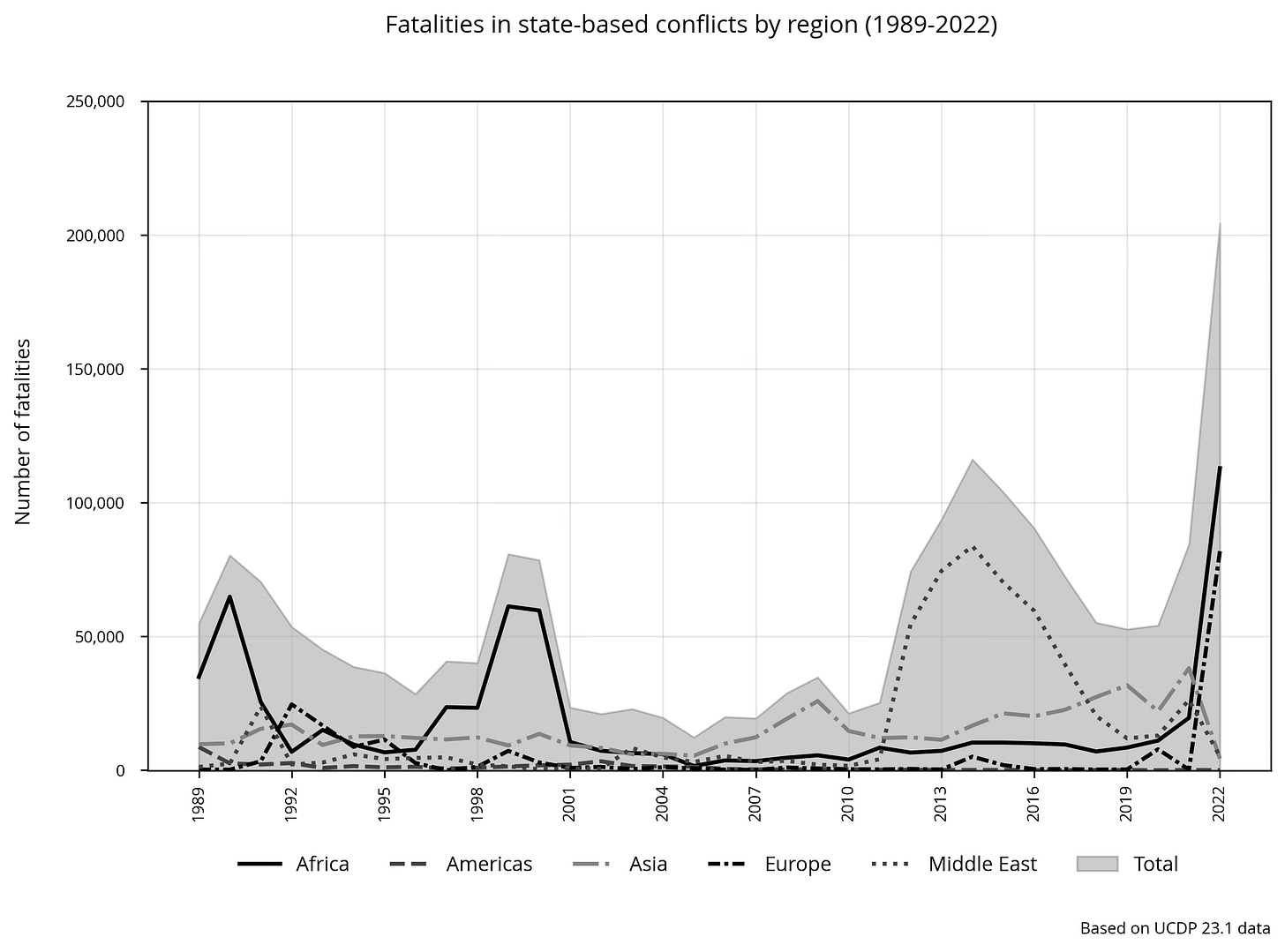

Fatalities in state-based conflicts by region (1989-2022)

Hopes for accountability for the gravest crimes under international law are becoming increasingly distant, as Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, Myanmar, Ethiopia, Sudan, and now Gaza, among many other examples, illustrate. Momentum in favor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) died long ago, as did the idea of a “responsibility to protect” (“R2P”) to prevent mass atrocities. Democracy around the world, we are told, has entered its 15th year of uninterrupted decline, and given the devastating impact that social media have had on the public sphere over the last two decadres, we can only brace for what AI will do for the most effective brain high jacking invention since Hamlin’s Pied Piper.

The Creation: Facts and Myths

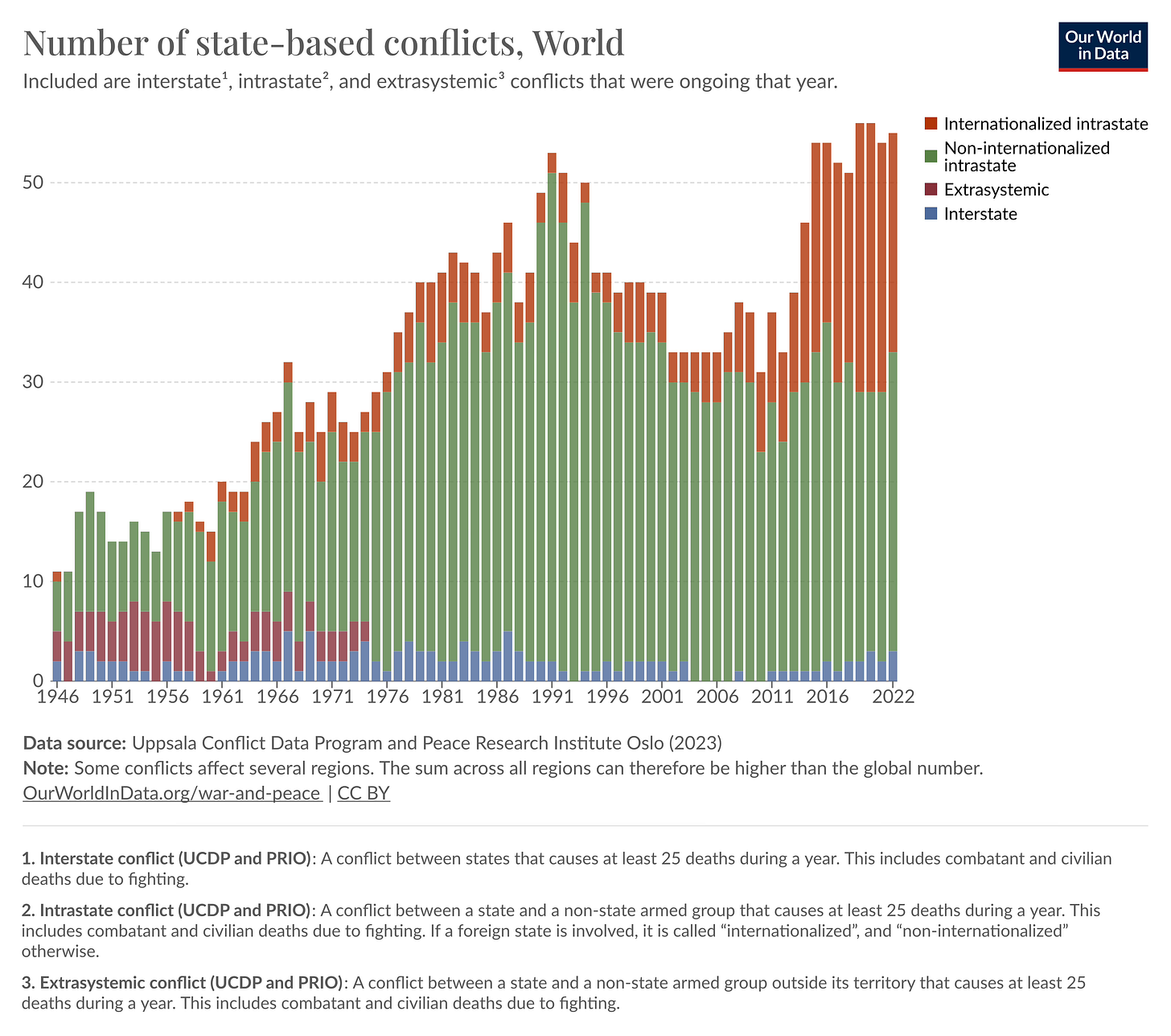

It was always a wager, of course, to reconcile a system build on the supremacy of state sovereignty with respect for international law—which by definition places limits on said sovereignty. It was even more of a long shot to make issues inherently domestic and political, such as human rights, as a rubric of international diplomacy, or to impose restraining principles in the conduct of armed conflicts. But enshrining sovereignty was the price to pay for countries to join the international system, and in truth has proven over time effective in limiting inter-state conflicts and protecting small countries from being gobbled up by larger ones, as per the practice until then. (On this last point, see Oona Hattaway and Scott Shapiro convincing statistics in The Internationalists : How a Radical Plan to Outlaw War Remade the World.)

Number of State-Based Conflicts, 1946-2022

It is equally true that the commonly held view that the devastation of World War 2 provoked a collective awakening about the horrors of war and led to the desire to establish a “liberal international order” with human rights, democracy, and the rule of law as key principles is overly Western-centric. For the ambers of bombed-out Europe and Asia had not yet cooled down that European countries were launching vicious anti-decolonization wars that resulted in millions of deaths, while top American military leaders were advocating for the use of nuclear bombs in the Korean war (which still resulted, sans nukes, in over 5 million deaths). And while the U.S. entanglement in Vietnam is well-known, many of Europe’s murderous colonial wars aren’t. One example amongst many: between 1947 and 1949, the French killed up to 100,000 people in Madagascar—2 percent of the entire population—to put down an insurrection. So much for the lessons supposedly drawn about war’s horrors.

Village burned by French Soldiers (Madagascar, 1951)

It might also be worth remembering that Europe’s much vaunted “Long Peace” (Pax Europaea) after WW2 was not due solely to post-war humanistic enlightenment but in good part to a combination of mass deportation of minority populations (between 1944 and 1951, 20 million people were expelled, resettled or exchanged between states in Europe) and the stabilizing effect of mutual assured destruction in the nuclear age. As for the rest of the world, it enjoyed precious little peace overall, while also been the scene of recurring impulsive or ill-advised military interventions by the very architects and stewards of the new “rules-based order”.

Yet, few would argue that a world without any truly global fora, institutions and, yes, international law, would decrease the risk and occurrence of armed conflicts (both inter and intra states), humanitarian crises, large-scale economic predation, or human rights violations.

That the likes of China and Russia are actively seeking a reinterpretation of the foundations of the current order—one that would stamp out any type of mutual accountability mechanisms, not to mention human rights standards—is evidence enough (to me at least) that norms have some real-world effect. What’s more, it is difficult to imagine how to common existential threats, global warming above all, can be addressed without some sort of structured global system.

What Does International Law Really Do?

Since moving (temporarily) from a practitioner role to the rarified world of scholarly pursuits, I have been forced to confront that endlessly debated issue: what is the relationship between norms and the real world, or, in this precise case, between international human rights norm and actual human rights change? As I quickly discovered, examining this issue opens a Pandora box of disputes that fill entire libraries: Does international law matter? How did the international human rights regime come about? And since it is unenforceable (bar the occasional military intervention—which generally comes with its own legality problems), how do we account for its real-world effect?

Here, I must confess that during two decades of work as a practitioner I never cared much about the UN human rights mechanisms—after all, the UN as a whole is not exactly known for its effectiveness. Even if the UN was highly efficient, its human rights component is minuscule, averaging only about 2 to 3 percent of its budget. While the standards are good (the international human rights covenants signed by states and all their marginalia ), and offer a common platform for trying to moralize the conduct of states, it’s (almost) never the UN itself that is the driving force behind implementation. I am not alone in thinking this way: the two big international human rights organizations I have worked for, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, have hundreds of staff working on anything from research to communication but employ only a couple of staff to do “UN advocacy”.

Over the past year, though, I have come to recognize that even though its real-world effects are hard to grasp, the demise of the UN Charter-based human rights system would have devastating consequences on state behavior, who would feel even freer to ignore human rights imperatives.

A “Stop!” Sign Can’t Actually Stop You

The way I try to present this apparent paradox to students is by drawing an analogy with road signalization. A “Stop!” sign, or any other road sign, doesn’t actually do anything on its own. It certainly doesn’t physically stop a vehicle, or prevent it from ignoring said sign. Some are entitled to override them under certain circumstances, and often abuse that privilege (e.g. the police, high officials). Penalties for violations have little impact on wealthy drivers, to whom the fines are inconsequential. The degree to which the general population complies with road signs depends on many factors, but an overriding one is the level of prosperity of the place (country, region, town…). The wealthier the place, the most resources it can devote to deployment, enforcement, and education. Places with weak governance or undermined by street-level corruption are generally worse at enforcing rules of the road—or curbing human rights violations.

International human rights law is the same! It doesn’t do anything on its own; it is widely seen as a hindrance on “getting things done”; it is routinely disregarded; and it is a lot more comfortable to point out at how terrible others are as opposed to being examined by them. Most importantly, compliance largely depends state capacity, most often correlated to the level of economic development (on this correlation see this excellent recent paper – or, if you have time, Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson’s The Narrow Corridor).

Yet, in the same way that the predictable result of doing away with road signs would be pandemonium and a lot more road casualties, doing away with the UN human rights system and the international laws and standards that emanate from it would result in a much, much, worsened world. (More on this in a subsequent post).

Perhaps the most difficult challenge for the human rights community today is to find a way to defend the existing system from crumbling down, while at the same time addressing the fact that, from the very beginning, this was a two-tier system in which the West was expected to get a free pass.

Dean Acheson’s Present at the Creation illustrates the point.

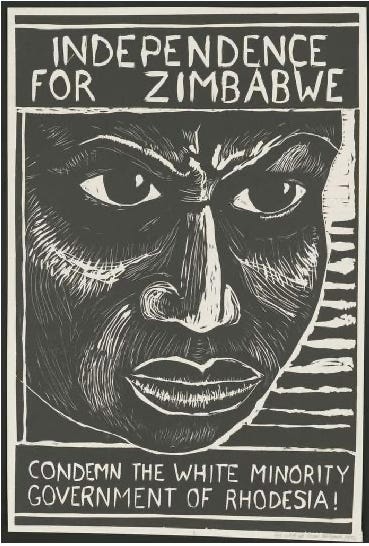

The ardent American internationalist who writes in his memoirs that “it is one of the principal aims of our foreign policy today to use our economic and financial resources to widen (…) human dignity, human freedom, and democratic institutions” is the same man who decries a few pages later that the United Nations, instead of being “an aid to diplomacy” has become “a possible instrument of interference in the affairs of weak white nations, as Rhodesia is experiencing as I write”.

Rhodesia, as we remember, was an openly white supremacist state, whose very reason for its existence was to prevent the black majority from gaining power in what would eventually become Zimbabwe.

As concerned as we are about being “present at the destruction” today, and as much as we must fight to prevent it, it is worth remembering that seeds of destruction were there from the beginning. The battle is as much for the human rights system against its enemies as against aspects of the power system that gave rise to it. And that’s one reason this fight can’t be left to states alone, no matter how liberal they claim to be.